A new guest blog by our Croatian Japan Fan, Japanologist Klara! This time she talks about good manners and etiquette in Japan: Bushido.

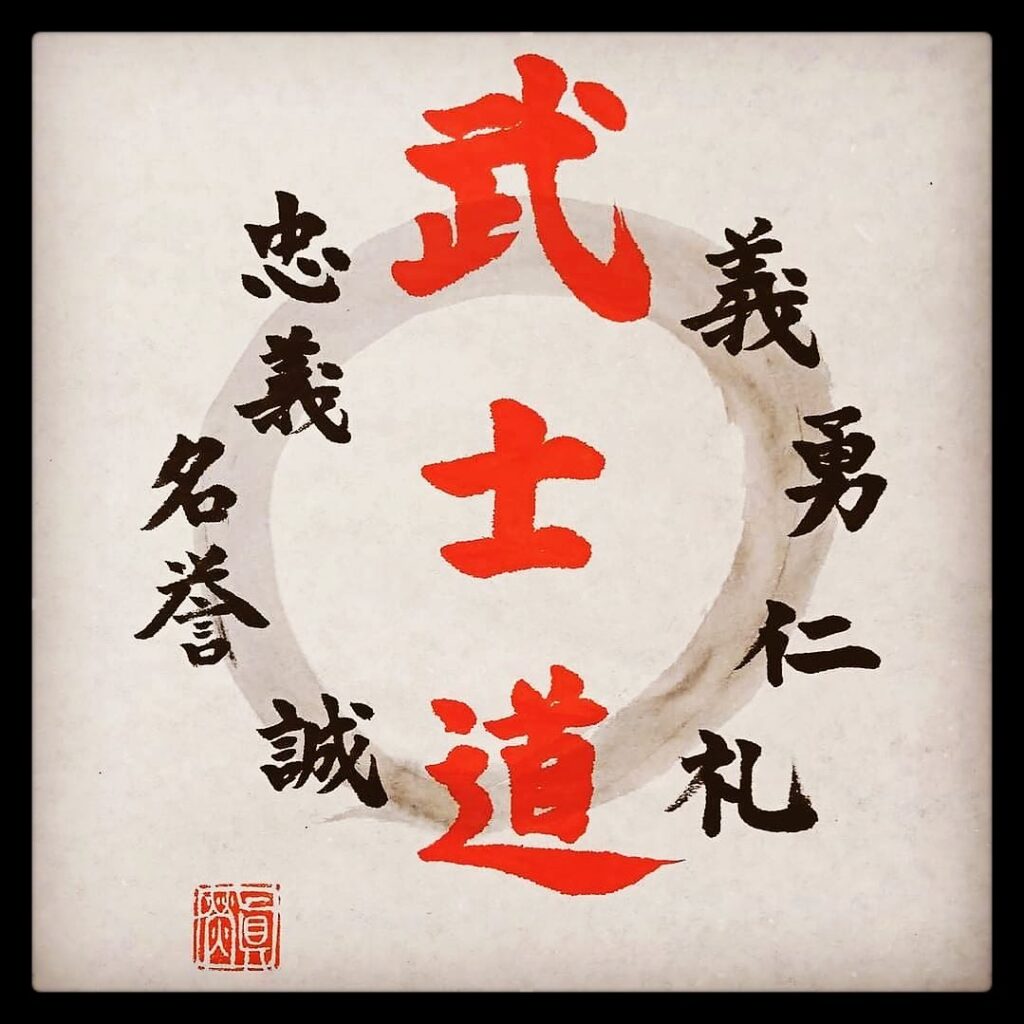

Bushido(武士道、”the way of the warrior”) was the code of conduct for Japan’s warrior classes. There are multiple Bushido types which evolved significantly through history.

The word “bushido” comes from the Japanese roots “bushi(武士)” meaning “warrior,” and ” do 道” meaning “path / way.” It translates literally to “way of the warrior.”

Bushido was followed by Japan’s samurai warriors and their precursors in feudal Japan, as well as much of central and east Asia. The principles of bushido emphasized honor, courage, skill in the martial arts, and loyalty to a warrior’s master (daimyo) above all else. It is somewhat similar to the ideas of chivalry that knights followed in feudal Europe. There is just as much folklore that exemplifies bushido—such as the 47 Ronin of Japanese legend—as there is European folklore about knights.

You can identify a strong Budoka by observing his/her etiquette, manners, posture and movements.

What Is Bushido?

Bushido is a code of conduct that emerged in Japan from the Samurai, or Japanese warriors, who spread their ideals throughout society. They drew inspiration from Confucianism, which is a relatively conservative philosophy and system of beliefs that places a great deal of importance on loyalty and duty, but it was more an ethical system, rather than a religious belief system.

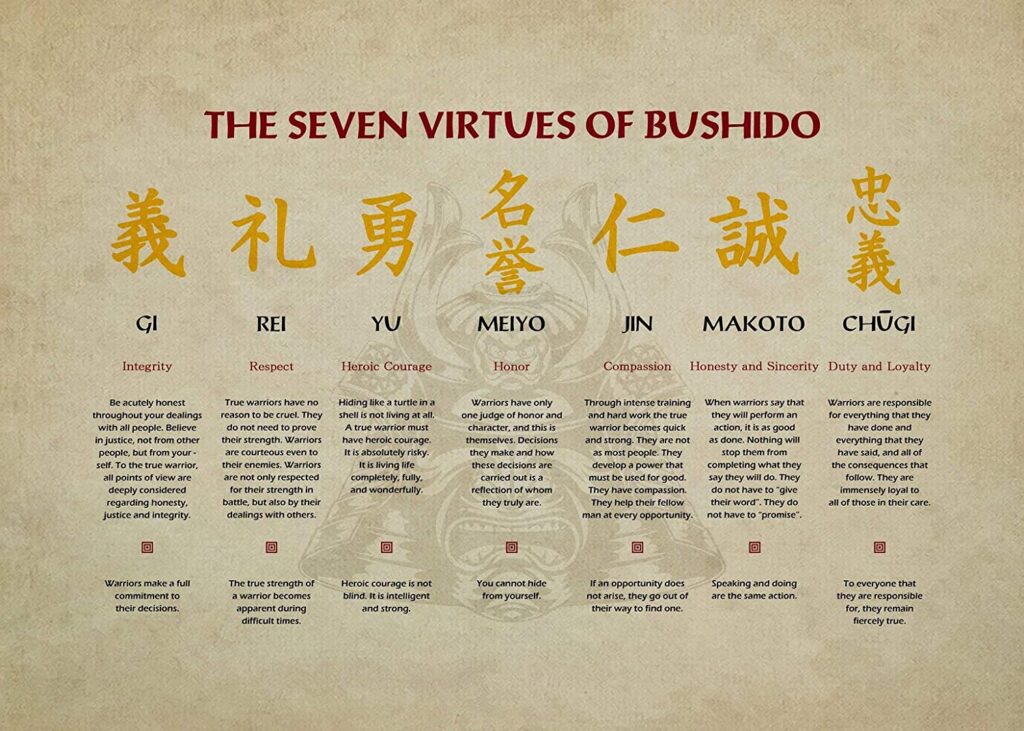

The Bushido code contains eight key principles or virtues that warriors were expected to uphold. Those are:

Justice 義: a core value of the Samurai; requires reflecting on what is fair and upholding the value of upstanding moral character

Courage勇: requires the strength not only to perceive but also to act

Compassion仁: the ability to manifest love and sympathy through patience; requires attempting to see the world from the perspective of another

Respect礼: acknowledging our regard for the experiences and feelings of others; politeness must be employed

Integrity誠: maintaining integrity – living honestly and sincerely

Honor名誉: must acknowledge our moral responsibilities

Loyalty忠義: when fealty is given to another, this must not be abandoned even under difficult circumstances

Self-control自制: adhering to this code under all circumstances, when with others and when alone

Many samurais believed that they were excluded from any reward in the afterlife or in their next lives, according to the rules of Buddhism, because they were trained to fight and kill in this life.

The ideal samurai warrior was supposed to be immune from the fear of death. Only the fear of dishonor and loyalty to his daimyo motivated the true samurai. If a samurai felt that he had lost his honor (or was about to lose it) according to the rules of bushido, he could regain his standing by committing a rather painful form of ritual suicide, called “seppuku.”

While European feudal religious codes of conduct forbade suicide, in feudal Japan it was the ultimate act of bravery. A samurai who committed seppuku would not only regain his honor, he would actually gain prestige for his courage in facing death calmly. This became a cultural touchstone in Japan, so much so that women and children of the samurai class were also expected to face death calmly if they were caught up in a battle or siege.

History of Bushido

As early as the eighth century, when armed supporters of wealthy landowners began to be known as Samurai. Toward the end of the 12th century, power in Japan shifted and the Kamakura Shogunate military dictatorship was established. During this time, leaders popularized the use of Samurai and codified their privileged status.

In the middle period between the 13th to 16th centuries, Japanese literature celebrated reckless courage, extreme devotion to one’s family and to one’s lord, and cultivation of the intellect for warriors. Most of the works that dealt with what would later be called bushido concerned the great civil war known as the Genpei War from 1180 to 1185, which pitted the Minamoto and Taira clans against one another and led to the foundation of the Kamakura Period of shogunate rule.

In the Tokugawa period, the Japanese art forms popular among the Samurai began to flourish. These included tea ceremonies, rock gardens, flower arranging, and a unique Japanese painting style that was developed during Edo period. This was a time of introspection and theoretical development for the samurai warrior class because the country had been basically peaceful for centuries. The samurai practiced martial arts and studied the great war literature of earlier periods, but they had little opportunity to put the theory into practice until the Boshin War of 1868 to 1869 and the later Meiji Restoration.

As with earlier periods, Tokugawa samurai looked to a previous, bloodier era in Japanese history for inspiration—in this case, more than a century of constant warfare among the daimyo clans.

Modern Bushido

After the samurai ruling class was abolished in the wake of the Meiji Restoration, Japan created a modern conscript army. One might think that bushido would fade away along with the samurai who had invented it. In fact, Japanese nationalists and war leaders continued to appeal to this cultural ideal throughout the early 20th century and World War II. Echoes of seppuku were strong in the suicide charges that Japanese troops made on various Pacific Islands, as well as in the kamikaze pilots who drove their aircraft into Allied battleships and bombed Hawaii to start off America’s involvement in the war.

Today, bushido continues to resonate in modern Japanese culture as well as in dojo / budo cultures abroad. In addition to impacts on military performance, media, entertainment, martial arts, medicine and social work, it stress on courage, self-denial, and loyalty has proved particularly useful for corporations seeking to get the maximum amount of work out of their “salarymen.”

Therefore, this is at the origin of the industrial harmony (労使協調) ideology of modern Japan. It allowed the country to become, with the Japanese economic miracle, the economic leader of Asia in the post-war years of the 1950-1960s.

The Bushido spirit exists in Japanese martial arts as well (Budo, Iaidō, Kendo, Kyudo…). Although the modern Bushido is guided by eight virtues, that alone is not enough. Bushido not only taught him how to become a soldier, but all the sages of life. The warrior described by Bushido is not a profession but a way of life. It is not necessary to be in the army to be a soldier. The term “warrior” refers to a person who is fighting for something, not necessarily physically. Man is a true warrior because of what is in his heart, mind, and soul. Everything else is just tools in the creation to make it perfect. Bushido is a way of life that means living in every moment, honorably and honestly. All this is of great importance in the life of a soldier, both now and in the past.

Bushido types

Multiple Bushido types have existed through history. The code varied due to influences such as Zen Buddhism, Shinto, Confucianism as well as changes in society and on the battlefield.

Ancient Bushido: during the Heian-Kamakura Period (794-1333); the samurai at that time were called “tsuwamono” (兵)”; the Genpei War (1180–1185) is exemplary of the ancient bushido type

Sengoku Bushido: during the Muromachi-Azuchi Period (Sengoku period) (1336-1603); battles occurred frequently in various places and the purpose was to expand one’s power; honor, weaponry and warfare were valued of utmost importance in Japanese culture

Edo Bushido: early to late Edo Period (1603 – 1868); the samurai could no longer obtain merit on the battlefield; as per Confucianism, it was valued to work for morals and the public, not for personal reasons

Meiji Bushido: Meiji to mid Showa Period (1868-1945); emperor worship with an emphasis on loyalty and self-sacrifice; the book Bushido: The Soul of Japan by Nitobe Inazō

Contemporary Bushido: 1950-today; continues to exist in various forms in for example business, communication, martial arts and as a way of life; „bushido spirit“.

Read more:

Szczepanski, Kallie. “Bushido: The Ancient Code of the Samurai Warrior.” ThoughtCo. (accessed May 20, 2021). Or via these more general websites:

Invaluable

Artofmanliness.com

Britannica.com

History.com

The meaning of Bushido has evolved, changed, and even been edited to a certain extent (particularly when examining WW2 Japan). But what did it mean to the Warring States Japanese? Was it all about personal honour, committing ritual suicide to avoid dishonour, etc? Or is there more to it.

Risuke Otake, Sensei of the Katori Shinto Ryu school, offers a nutshell view of how the Warring States interpreted Bushido (6:23-7:40):

“Outside of Japan, people think that Bushido is synonymous with hara-kiri (ritual suicide). Actually, the meaning of Bushido is to achieve something in the world and then to be able to throw away this body, and to accept death. But this concept is very easily misunderstood. It’s really quite different from just going out and dying. if you fail to achieve something and say “Oh, I must kill myself”, it’s not a very productive way of thinking. Bushido rejects that irresponsible way of thinking.If you tried to perform some act and failed, there is also in Bushido the concept of continuing to live even though you may have to live in shame. If there is a chance to right the wrong you’ve done, then you should do so. This is the real Bushido.”