This article was written by a member of the Japan Fans community.

Two years ago, I embarked on a challenging journey to learn the Japanese language. This was in no small part aided by the wonderful Japan Fans community in Utrecht, but also by my profound love for Japanese literature. I often find Japanese literature, even when translated, to be captivating, with enigmatic storylines, unconventional narrative structures, and deep philosophical insights. The strangeness and originality of Japanese literature are unparalleled in my experience. To kick off what will hopefully become a series, let’s start with a brief rundown of Japan’s rich literary landscape, along with some recommendations for those eager to explore it. In future posts, we will explore specific time periods, genres, and authors.

Japanese literature boasts a long and colourful history, from ancient texts like the Kojiki (古事記) to contemporary authors like Haruki Murakami (村上春樹). What sets it apart is its distinct style: compared to stories from other parts of the world, Japanese literature might seem less overt and sensationalist, favouring subtlety and an emphasis on the undercurrents of human emotion. This could be seen as a reflection of the Japanese cultural concept of kuuki wo yomu (空気を読む) or ‘reading the air.’ Japan’s nuanced storytelling, particularly present in earlier works, might initially appear understated, especially if you’re accustomed to the directness of Western literature. But think of it as a form of ‘quiet introspection’, like silently enjoying a Zen—garden.

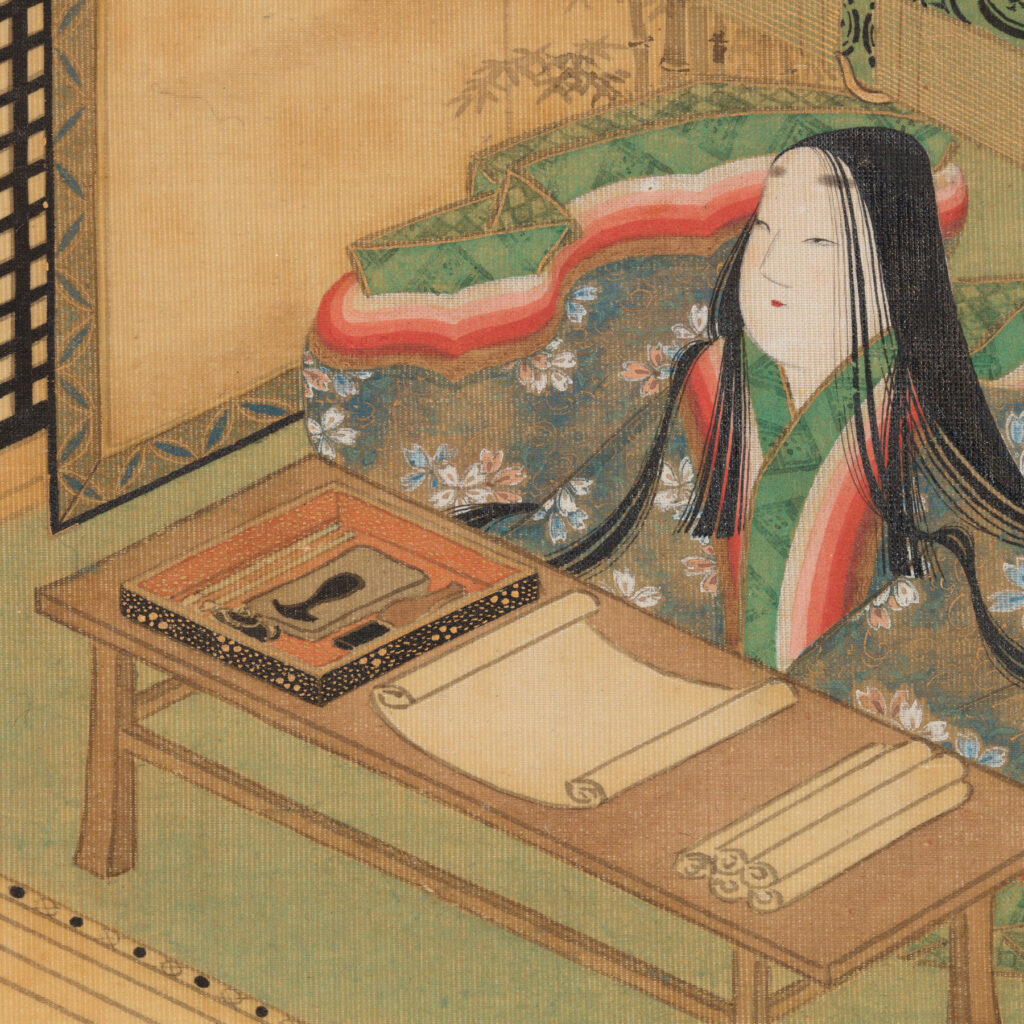

Japanese literature traces its roots back to the 5th century, when Chinese characters were adopted into an early writing system, followed by foundational texts like the Kojiki (古事記, 712). For enthusiasts of classic literature, however, I recommend The Tale of Genji (源氏物語, early 11th century) as an ideal entry point. The Heian period (平安時代, 794 – 1185), denoting “peace,” marks an era of elegance and artistry in Japan’s literary history, largely sponsored by its imperial court. A significant portion of this literature was penned by aristocratic women, who were pivotal to the era’s cultural life of the time. The Tale of Genji by Lady Murasaki Shikibu (紫式部) —a pseudonym, as her real name remains a mystery—is among the most revered works from this time period. It tells of the life of Genji, a royal heir, entwining his romantic pursuits and political (mis)fortunes, providing a rich portrayal of Heian Japan’s lavish court life and complex social interactions. The subsequent Kamakura period (鎌倉時代, 1185–1333), characterised by civil war and the rise of the shogunate and samurai class, is vividly depicted in The Tale of the Heike (平家物語, 12th– 13th century). This epic chronicles the Taira (平) clan’s ascension and fall, capturing the era’s martial ethos and the fleeting nature of fame and power.

Transitioning through the vibrant Edo period (江戸時代, 1603–1868), celebrated for haiku (俳句) – such as by Matsuo Basho (松尾芭蕉, 1644–1694) – and the dramatic kabuki (歌舞伎) theatre, we fast-forward to a pivotal moment in 1867. This year marks the end of centuries of samurai governance, initiating the Meiji period (明治時代, 1868–1912). This era is notable for Japan’s rapid evolution from a traditional feudal society to a significant industrial power. Amidst this transformation, Japanese literature also flourishes, integrating new global influences while maintaining its distinctive cultural identity. While I have yet to read it, The Makioka Sisters (細雪, or sasameyuki, meaning ‘light snow’, 1943 – 1948) by Junichiro Tanizaki (谷崎 潤一郎) supposedly perfectly captures this transition. The story is set in the years leading up to World War II and focuses on the lives of four sisters trying to find their place in a Japan that’s changing fast.

Two standout authors from this time are Natsume Soseki (夏目漱石) and Yasunari Kawabata (川端康成). Soseki’s books, like I Am a Cat (吾輩は猫である, 1905–1906), poke fun at the quirks of people in Meiji Japan through the eyes of a witty cat. Kokoro (こころ, 1914), or ‘Heart’, goes deeper, exploring a special bond between a student and his mentor, reflecting on personal and societal shifts. Kawabata, on the other hand, paints his stories with delicate strokes, creating beautiful, sometimes sad tales. His Snow Country (雪国, 1935–1948) is a story about a love affair between the wealthy Shimamura and a geisha.

Other notable authors are Shusaku Endo (遠藤周作) and Yukio Mishima (三島由紀夫), who continue to dive into the struggles between old traditions and new ways. Worthwhile mentions are Endo’s Silence (沈黙, 1966), a gripping tale about Jesuit priests from Portugal in 17th-century Japan facing tough choices about their faith, and Mishima’s The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea (午後の曳航, or gogo no eiko, meaning ‘afternoon tow’, 1963).

Finally, we step into the realm of contemporary Japanese literature, which has become rich with diverse voices and innovative narratives that challenge more traditional boundaries found in Japanese literature. There is so much to get into here, that I will limit it for now to some of my favourite works I’ve read so far :-).

Naturally, I couldn’t write on Japanese literature without mentioning Haruki Murakami (村上春樹), and for a long time he was among my all-time favourite authors. While I’ve become more critical of his work in recent years, mainly because of how he portrays female characters, his ability to seamlessly blend the mundane with the fantastical is addictive. Of course, there is Norwegian Wood (ノルウェイの森, 1987), often recommended as an introduction to his work, but it’s somewhat of an outlier, lacking the magical realism aspects that otherwise characterise his style. Kafka on the Shore (海辺のカフカ, 2002), on the other hand, is a personal favourite of mine: imagine philosophical musings with a talking cat, unexpected characters like Colonel Sanders (yes, the one from KFC), and a rainstorm of fish.

Other wonderful modern recommendations are Kitchen (キッチン, 1988) by Banana Yoshimoto (吉本ばなな), The Memory Police (密やかな結晶, 1994) or The Housekeeper and the Professor (博士の愛した数式, 2003) by Yoko Ogawa (小川洋子), and Out (アウト, 1997) by Natsuo Kirino (桐野夏生). Newer on the literary scene is Sayaka Murata (村田沙耶香), who writes wonderfully weird, yet sometimes disturbing novellas such as Convenience Store Woman (コンビニ人間, 2016) and Earthlings (地球星人, 2018) (warning: not for the faint of heart!).

These books will give you a rough initial idea of what Japanese literature has to offer, as it continues to reach a growing audience worldwide. But it’s also only just scratching the surface – there’s a whole world of Japanese literature out there waiting to be discovered, not to mention the exciting world of Manga (yes, I’d argue some of it has great literary value too)! If any of these books caught your eye, or if you’ve got some favourites of your own, I’d love to hear about it! And hey, if you’re based in or around Utrecht and looking to dive deeper into Japanese literature, why not join our book club? We aim to pick a new book every couple of months and it’s a great way to connect and share our thoughts. For more info, just get in touch with Japan Fans on this site.