As the Japan Fans Utrecht wish to form friendship bonds with Japan Fans from all over the world, we are very happy to announce this fourth guest blog written by Klara Friščić. Klara is a Japan Fan from Croatia who graduated in Japanese Language and Culture from the universities of Pula (Croatia) and Kyoto (Japan). In this blog, Klara teaches us some History and Culture of the Ainu, based on her research this East Asian ethnic group indigenous to northern Japan.

History and Culture of the Ainu

Japanese: アイヌ, Ainu / Ezo (蝦夷)

Russian: Áйны, Áĭny

Ainu are an East Asian ethnic group indigenous to northern Japan, the original inhabitants of Hokkaido and some of its nearby Russian territories (Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands, Khabarovsk Krai and the Kamchatka Peninsula).

Origins

The Ainu have often been considered to descend from the diverse Jōmon people, who lived in northern Japan from the Jōmon period (c. 14,000 to 300 BCE). Recent research suggests that the historical Ainu culture originated from a merger of the Okhotsk culture with the Satsumon culture, cultures thought to have derived from the diverse Jōmon-period cultures of the Japanese archipelago.

History of the Ainu

Recent research suggests that Ainu culture originated from a merger of the Okhotsk and Satsumon cultures. It is said that Ainu-speakers descend from the Okhotsk people which rapidly expanded from northern Hokkaido into the Kurils and Honshu. These early inhabitants did not speak the Japanese language. They formed a society of hunter-gatherers, surviving mainly by hunting and fishing. They followed a religion which was based on natural phenomena.

Muromachi period (1336–1573): many Ainu were subject to Japanese rule. Disputes between the Japanese and Ainu developed into large-scale violence.

Edo period (1601–1868): The Ainu became increasingly involved in trade with the Japanese who controlled the southern portion of the island and contact between Japanese and Ainu became more extensive, but it also led to conflict which occasionally intensified into violent Ainu revolts. Throughout this period Ainu groups competed with each other to import goods from the Japanese, and epidemic diseases such as smallpox reduced the population.

In the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the 19th century the shogunate took direct control of southern Hokkaidō, which lead to the following.

⦁ Ainu men were deported to merchant subcontractors for five and ten-year terms of service

⦁ had to drop their native language and culture and become Japanese

⦁ Ainu women were separated from their husbands and forcibly married to Japanese merchants and fishermen

⦁ Women were often tortured if they resisted rape by their new Japanese husbands

This policy of family separation and forcible assimilation, combined with the impact of smallpox, caused the Ainu population to drop significantly in the early 19th century.

Meiji restauration and later

In the 18th century, there were 80,000 Ainu, but in the 19th century, there were only about 15,000 Ainu in Hokkaidō, 2000 in Sakhalin and around 100 in the Kuril islands.

The beginning of the Meiji Restoration proved a turning point for Ainu culture. The Japanese government introduced a variety of social, political, and economic reforms in hope of modernizing the country in the Western style. One innovation involved the annexation of Hokkaidō.

The Japanese government takes the land where the Ainu people lived and placed it from then on under Japanese control. Also at this time, the Ainu were granted automatic Japanese citizenship, effectively denying them the status of an indigenous group – which made them more marginalized on their own land.

During this time, the Ainu were forced to learn Japanese, required to adopt Japanese names, and ordered to cease religious practices such as animal sacrifice and the custom of tattooing.

It was not until June 6, 2008, that Japan formally recognized the Ainu as an indigenous group.

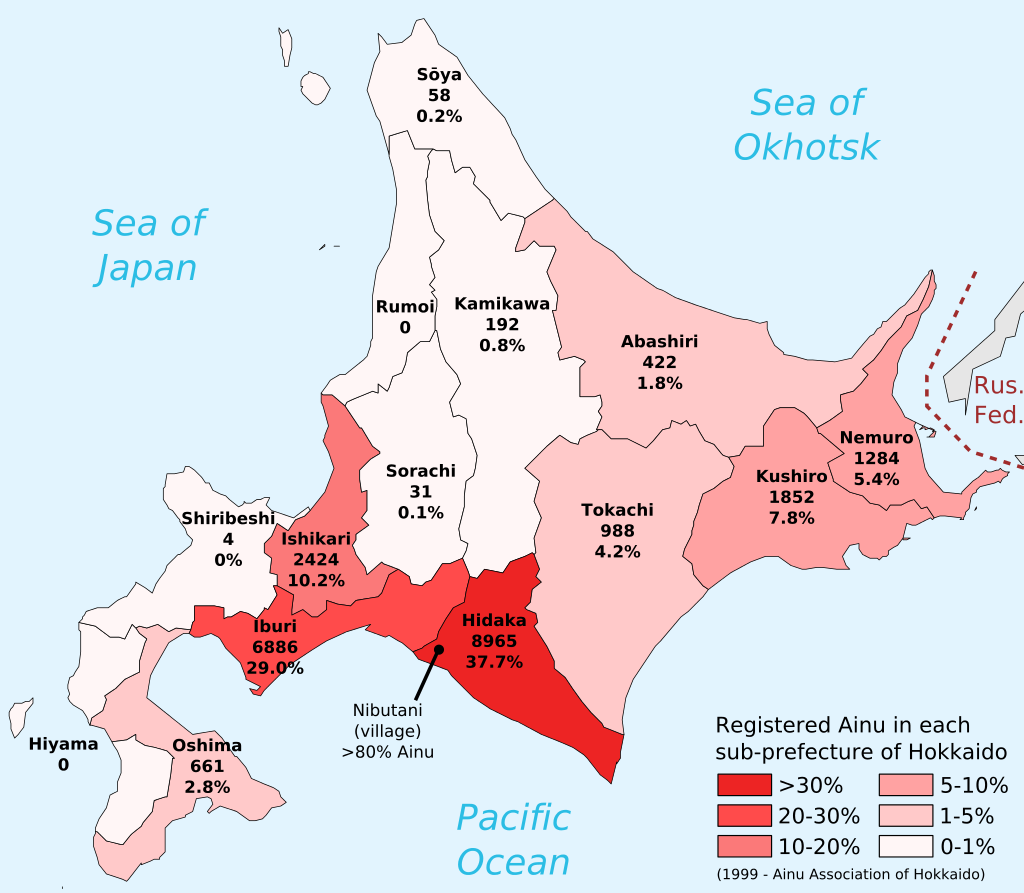

Some of the Ainu people still try to continue carrying out their language and culture and there are many small towns in the southeastern or Hidaka region where ethnic Ainu live such as in Nibutani (Niputay).

Many live in Sambutsu especially, on the eastern coast. In 1966 the number of “pure” Ainu was about 300.

Physical Description

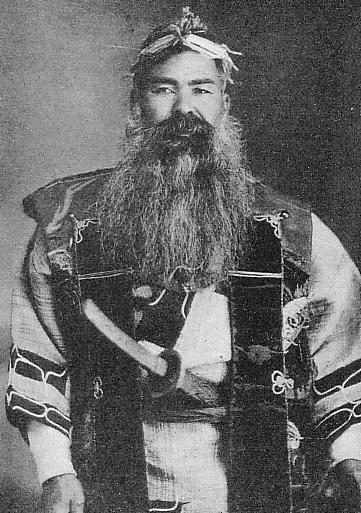

⦁ Ainu men have abundant wavy hair and often have long beards.

⦁ very few of them have wavy brownish hair

⦁ they are white, but because they work a lot outside, they are considered to be light brown

⦁ broad faces, beetling eyebrows, and large sunken eyes

A study by Omoto has shown that the Ainu are more related to other East Asian groups (previously mentioned as ‘Mongoloid’) than to Western Eurasian groups (formerly termed as “Caucasian”), on the basis of fingerprints and dental morphology.

Language

In 2008, there were estimate of fewer than 100 remaining speakers of the language; other research placed the number at fewer than 15 speakers. The language is characterized as “almost extinct”. As a result of this, the study of the Ainu language is limited and is based largely on historical research.

Despite the small number of native speakers of Ainu, there is an active movement to revitalize the language, mainly in Hokkaidō, but also elsewhere such as Kanto. Ainu oral literature has been documented both in hopes of safeguarding it for future generations, as well as using it as a teaching tool for language learners.

As of 2011 there has been an increasing number of second-language learners, especially in Hokkaidō, in large part due to the pioneering efforts of the late Ainu folklorist, activist and former Diet member Shigeru Kayano, himself a native speaker, who first opened an Ainu language school in 1987 funded by Ainu Kyokai.

Although some researchers have attempted to show that the Ainu language and the Japanese language are related but modern scholars have rejected the idea – Ainu is a language isolate. Most Ainu people speak either the Japanese language or the Russian language.

The Ainu language has had no indigenous system of writing, and has historically been transliterated using the Japanese kana or Russian Cyrillic. As of 2019 it is typically written either in katakana or in the Latin alphabet.

Culture of the Ainu

Traditional Ainu culture was quite different from Japanese culture. The Ainu culture can be included into a wider “northern circumpacific region”, referring to various indigenous cultures of Northeast Asia and “beyond the Bering Strait” in North AmericaNever shaving after a certain age, the men had full beards and moustaches.

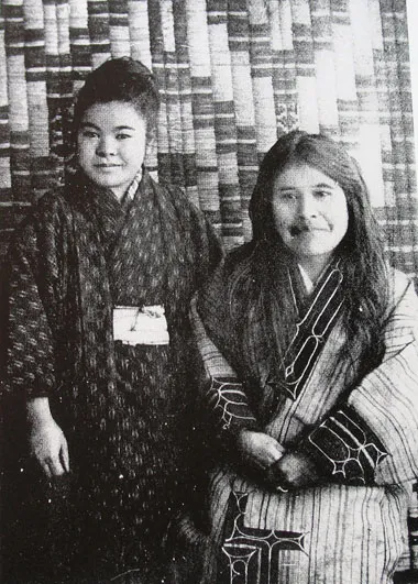

Men and women alike cut their hair level with the shoulders at the sides of the head, trimmed semicircularly behind.

The women tattooed their mouths, and sometimes the forearms. The mouth tattoos were started at a young age with a small spot on the upper lip, gradually increasing with size.

Their traditional dress was a robe spun from the inner bark of the elm tree, called attusi or attush. Various styles were made, and consisted generally of a simple short robe with straight sleeves, which was folded around the body, and tied with a band about the waist. The sleeves ended at the wrist or forearm and the length generally was to the calves. Women also wore an undergarment of Japanese cloth.

In winter the skins of animals were worn, with leggings of deerskin and in Sakhalin, boots were made from the skin of dogs or salmon.

Ainu culture considers earrings, traditionally made from grapevines, to be gender neutral. Women also wear a beaded necklace called a tamasay.

Their traditional cuisine consists of the flesh of bear, fox, wolf, badger, ox, or horse, as well as fish, fowl, millet, vegetables, herbs, and roots. They never ate raw fish or flesh; it was always boiled or roasted.

The men used chopsticks when eating; the women had wooden spoons.

Ainu cuisine is not commonly eaten outside Ainu communities; only a few restaurants in Japan serve traditional Ainu dishes, mainly in Tokyo and Hokkaidō.

A village is called a kotan in the Ainu language. Kotan were located in river basins and seashores where food was readily available, particularly in the basins of rivers through which salmon went upstream. A village consisted basically of a paternal clan. The average number of families was four to seven, rarely reaching more than ten.

Their traditional habitations were reed-thatched huts without partitions and having a fireplace in the center. There was no chimney, only a hole at the angle of the roof. The house of the village head was used as a public meeting place when one was needed. Another kind of traditional Ainu house was called chise.

Instead of using furniture, they sat on the floor; and for beds they spread planks, hanging mats around them on poles, and employing skins for coverlets.

Capital punishment did practically not exist, nor did the community resort to imprisonment. Beating was considered a sufficient and final penalty.

However, in the case of murder, the nose and ears of the culprit were cut off or the tendons of his feet severed.

Hunting

The Ainu hunted from late autumn to early summer.

A village possessed a hunting ground of its own or several villages used a joint hunting territory. Heavy penalties were imposed on any outsiders trespassing on such hunting grounds or joint hunting territory.

The Ainu hunted bear, Ezo deer, rabbit, fox, raccoon dog, sea eagles such as white-tailed sea eagles, raven and other birds.

The Ainu hunted with arrows and spears with poison-coated points. They obtained the poison, called surku, from the roots and stalks of aconites. The recipe for this poison was a household secret that differed from family to family.

They hunted in groups with dogs. Before the Ainu went hunting, they prayed to the god of fire, the house guardian god, to convey their wishes for a large catch, and to the god of mountains for safe hunting.

Fishing

Fishing was important for the Ainu. They largely caught trout, primarily in summer, and salmon in autumn, as well as “ito” (Japanese huchen), dace and other fish. Spears called “marek” were often used. Other methods were “tesh” fishing, “uray” fishing and “rawomap” fishing. Many villages were built near rivers or along the coast. Each village or individual had a definite river fishing territory. Outsiders could not freely fish there and needed to ask the owner.

Ornaments

Men wore a crown called sapanpe for important ceremonies. Sapanpe was made from wood fibre with bundles of partially shaved wood. This crown had wooden figures of animal gods and other ornaments on its centre. Men carried an emush (ceremonial sword) secured by an emush at strap to their shoulders.

Women wore matanpushi, embroidered headbands, and ninkari, earrings. Ninkari was a metal ring with a ball. Matanpushi and ninkari were originally worn by men. Furthermore, aprons called maidari now are a part of women’s formal clothes. However, some old documents say that men wore maidari. Women sometimes wore a bracelet called tekunkani.

Women wore a necklace called rektunpe, a long, narrow strip of cloth with metal plaques. They wore a necklace that reached the breast called a tamasay or shitoki, usually made from glass balls. Some glass balls came from trade with the Asian continent. The Ainu also obtained glass balls secretly made by the Matsumae clan.

Traditions

The Ainu people had various types of marriage. A child was promised in marriage by arrangement between his or her parents and the parents of his or her betrothed or by a go-between. When the betrothed reached a marriageable age, they were told who their spouse was to be.

There were also marriages based on mutual consent of both sexes. In some areas, when a daughter reached a marriageable age, her parents let her live in a small room called tunpu annexed to the southern wall of her house. The parents chose her spouse from men who visited her.

The age of marriage was 17 to 18 years of age for men and 15 to 16 years of age for women, who were tattooed. At these ages, both sexes were regarded as adults.

When a man proposed to a woman, he visited her house, ate half a full bowl of rice handed to him by her, and returned the rest to her. If the woman ate the rest, she accepted his proposal. If she did not and put it beside her, she rejected his proposal.

When a man became engaged to a woman or they learned that their engagement had been arranged, they exchanged gifts. He sent her a small engraved knife, a workbox, a spool, and other gifts. She sent him embroidered clothes, coverings for the back of the hand, leggings and other handmade clothes.

Men wore loincloths and had their hair dressed properly for the first time at age 15–16. Women were also considered adults at the age of 15–16. They wore underclothes called mour and had their hair dressed properly and wound waistcloths called raunkut and ponkut around their bodies. When women reached age 12–13, the lips, hands and arms were tattooed. When they reached age 15–16, their tattoos were completed. Thus were they qualified for marriage.

Religion of the Ainu

The Ainu are traditionally animists, believing that everything in nature has a kamuy (spirit or god) on the inside. The most important include Kamuy-huci, goddess of the hearth, Kim-un-kamuy, god of bears and mountains, and Repun Kamuy, god of the sea, fishing, and marine animals. Kotan-kar-kamuy is regarded as the creator of the world in the Ainu religion.

The Ainu have no priests by profession; instead, the village chief performs whatever religious ceremonies are necessary. Ceremonies are confined to making libations of sake, saying prayers, and offering willow sticks with wooden shavings attached to them. These sticks are called inaw (singular) and nusa (plural).

Nowadays Ainu assimilated into mainstream Japanese society have adopted Buddhism and Shintō, while some northern Ainu were converted as members of the Russian Orthodox Church.

If you like to read more about the Ainu people, Klara recommends the articles on these four web sites: BBC Travel, Minority Rights, Wikipedia, Britannica.