For the project “The Spirit of Kanji“, we interviewed Utrechters of Asian descent. One of those people was Toshio and you can read his interview below: Being a bisexual Japanese at home in Utrecht. The artwork will also be on display at the Japan Fans exhibition in ACU.

Under the title “The Spirit of Kanji“, the Japan Fans Foundation is doing artistic research on Utrecht residents of Asian descent. They will present the results of this research in interviews and kanji (Chinese characters) in various community centres, cafes and libraries in Utrecht, such as ACU. The Japan Fans Foundation aims to establish a centre for Japanese culture in Utrecht.

A bisexual Japanese at home in Utrecht

On a rainy afternoon in May 2021, I meet the man whom I will refer to as Toshio (敏夫). He was born and raised in Hachioji (八王子市), a city in the west of Tokyo prefecture, and came to the Netherlands as a student. First to Eindhoven, then to Delft. Eventually he found his permanent job and his great love in Utrecht.

“I knew nothing about the Netherlands,” says Toshio, “only that you could become an engineer there. Oh and that Miffy comes from there! All the girls in my class thought Miffy was cute.” And the boys? Toshio smiles shyly and looks away. “Maybe… but then they didn’t dare say it. At least, not to me. I think they sensed that I wasn’t a standard guy.”

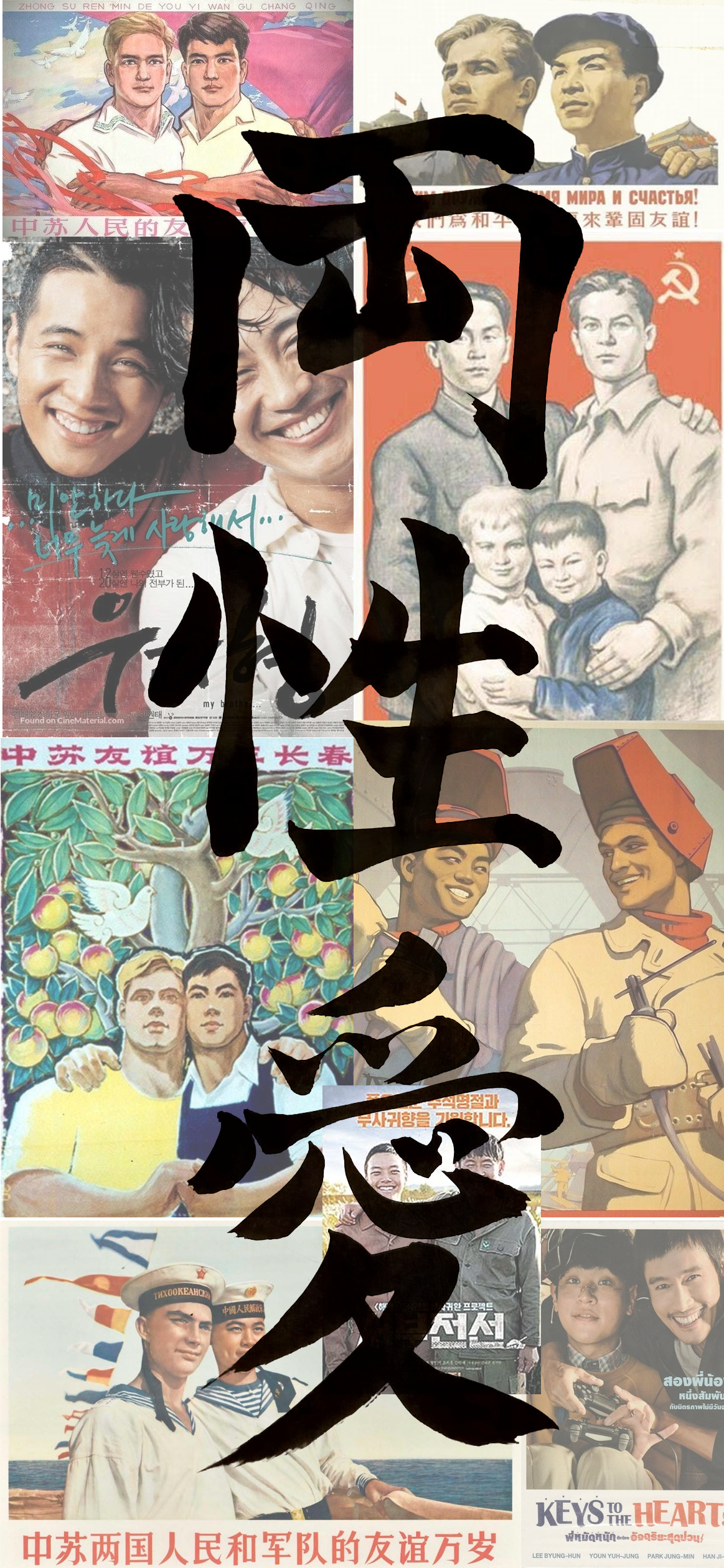

“In Asian cultures you don’t talk about sexuality. But when I saw pictures of boys together, for example on a film poster or in a book, I felt things. Things for which I did not know the word. I loved Korean films and for a while I collected film posters. The boys on them were usually brothers or ‘normal’ friends, so that wasn’t a problem. But when we were learning about China and the Soviet Union in history at school, I sometimes saw pictures of brotherhood that confused me. I didn’t look at them for too long. I tried to focus on my schoolwork.”

“When I fell in love with a woman for the first time, I felt relieved. She was a teacher at our school and I found her very exciting. But most of the crushes at that time were on boys and I was very ashamed of that. I think those emotions are a common thread in my life.” When we started our conversation, Toshio didn’t know which kanji he would choose. “That’s a bit… difficult for me,” he explained, “Because I don’t think like that. I don’t think: what do I like the most, what do I want the most? I just try to look around me at what’s needed, and meet it as best I can.”

Yet when Toshio saw his current wife, he knew immediately that he liked her. “I saw her on the street and it was like a movie, like time was slowing down and everything around her was blurred. At first I thought: ‘what a pretty boy’, but when she turned around… it was as if I was struck by lightning. She is small, flat as a board, and with very short hair. The kind of girl who would be called “garuson” in Japan, from the French word for boy, because she is boyish. I fell for her like a log, but it took some persuading before she wanted to be my girlfriend!”

One of the reasons his wife initially hesitated was because she thought Toshio looked so dull and colourless. “The young generation now seems freer,” muses Toshio, “they dress more androgynously and question the norms of masculinity: if women can wear trousers, why should only girls and women be allowed to wear skirts and dresses? That was not an issue at all in my time. How attractive you were as a man depended on your otokorashisa – your masculinity – which the outside world could judge by your reliability, your status, your loyalty and your productivity. Now women look more at what hairstyle a man has and how he dresses.”

So in Japan, too, the male/female ratios seem to be shifting. But appearances can be deceiving and rebellious clothing can also be an adolescent phase. “There are more and more iku-men – men who raise their children – but the main Japanese archetype of masculinity is still the office worker: he has a steady job, in a suit and with a briefcase, and uses it to support his family. That is a picture that just doesn’t fit me.

In the Netherlands, Toshio found other pictures, boxes and examples. Yet it is not the case that he prefers the Netherlands to Japan. “I will always be Japanese, because I love Japan and am proud of my background and culture. But as a bisexual Japanese person, I now feel at home in Utrecht.”

The name Toshio is a pseudonym.